In our guest post for December, Emma Stanbridge (PhD Candidate, Keele University) explores a diamond theft outside the Opera House, and the dangers lurking on the margins of Mary Hamilton's brilliant social world.

An attack outside the Opera House

On 22nd May 1784, The General Evening Post reported that James Napier was, ‘committed to Newgate, on a charge against him on oath for feloniously assaulting the Hon. Albinia Hobart, on the highway, in the parish of St. James, Westminster, putting her in fear, and taking from her person a diamond ear-ring’.[1] A report, which appeared a few days later in the Morning Chronicle on 25th May, provides further detail, stating that Napier was convicted of ‘feloniously assaulting the Hon. Mrs. Hobart, near the door of the Opera House, and with violence tearing from her ear a diamond ear-ring, which was afterwards found dropt in her hair’.[2]

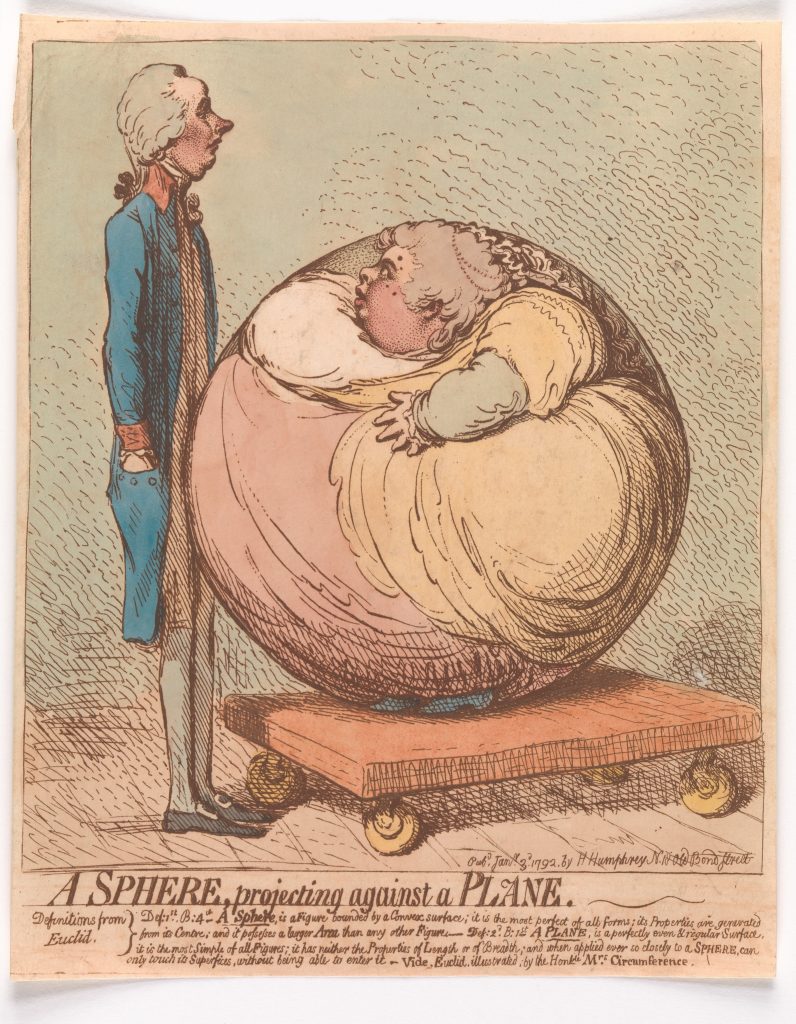

James Gillray (1792), "A Sphere, Projecting Against a Plane".

The image depicts a spherical Hobart in contrast to the slim and angular Prime Minister, William Pitt.

(Image Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Albinia Hobart was a British celebrity, who would later in 1793 become the Countess of Buckinghamshire. Hobart was often the victim of satirical illustrations and was perhaps most notably the subject of those by James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson. However, Hobart’s own testimony of the robbery paints a more affecting portrait:

I was going out of the Opera house on Saturday fortnight, at the King's door as I was going into my coach, I felt a person take hold of my ear, and pull my ear-ring, and endeavour to pull it out […] it was separated from my ear, it was a gold ear-ring set with diamonds; the tearing my ear down hurt me very much; my ear bled, I screamed out, and missed my ear-ring; I then got into the coach and got home, after I went home my ear-ring was found in my hair; I did not see the prisoner at all.[3]

The account of the trial reveals that an Edmund Lascells (possibly Edward Lascelles, later 1st Earl Harewood) did see Napier, who is described in the Old Bailey proceedings as a tailor from the nearby parish of St. Anne’s Soho.[4] Lascells testified that he ‘saw him when she screamed out with his hand up to her ear’.[5] The General Evening Post reported later that year that Napier had been sentenced to death, and provided an account of the execution, which took place on the 1st September.[6] Condemning a convict to death was a common sentence, especially in the years following the Gordon Riots.

As Hitchcock and Shoemaker state, during this period, executions increased ‘dramatically’:

23 were executed in 1779, there were 97 executions in 1785, the bloodiest year in the century. Not only were more convicts hanged, but they formed a growing percentage of all those sentenced to death, reaching 64.2 per cent of the condemned in 1785 and 81.4 per cent in 1787. This was a direct result of a decision by the Home Secretary in September 1782 to refuse to grant pardons (as had often occurred previously) to those convicted of robberies and burglaries ‘attended with acts of great cruelty’.[7]

A ‘new species of robbery’

On 13th May, Mary Hamilton recorded an account of the robbery in her diary. Hamilton states that there was ‘much talk’ of the incident during her visit to Charlotte Walsingham, writing

ye. other Eveg as Mrs. Hobart was coming out a great Assembly – a Man hit her a violent blow on ye. temple & Pull’d her Earring quite through her Ear – ye. Gentleman who was handing her was surprised to hear her scream out & turning round saw the blood pouring down her Neck for the Ear was torn quite through.[8]

With the exception of Hamilton’s detail of ‘a violent blow to the head’, which is not mentioned by Hobart in her testimony, both describe the violent intensity of the event as Hobart ‘screamed out’ after her ear was ‘torn through’ and pouring with blood. Hamilton’s account in particular reveals a deeper anxiety about this ‘new species of Robbery’, which was gaining prominence in London, whereby thieves stole ‘the Diamond Pins out of ye. ladies heads as they were getting into their Carriages’ (HAM/2/10, 39).

James Carrick, "A compleat and true account of all the robberies committed by James Carrick, John Malohni and their accomplices […]" (London, 1722), p.1 [detail].

(Image Credit: Eighteenth-century Collections Online)

when the arrests and executions of highway robbers became too frequent, his gang turned to ‘the novelty of making these attempts in the publick streets on foot, with the ease of going thro with them successfully, from the surprize they would cast those into whom they should be made upon’[9]

Though highwaymen may have been casting ‘surprise’ on their victims in the ‘publick streets’ for some time, this act is nevertheless shocking to Hamilton. In fact, the attack on Hobart is the only topic of conversation recorded in her entry for the evening of 13th May. The brutality of the act of taking the earrings by tearing them directly from the victim’s body is shocking in itself, but also because the robbery takes place within the crowd outside the theatre. The theatre is a space in which Hamilton and her contemporaries could expect behaviour to be, to an extent, socially regulated. However, the crowd also offers intimate proximity to strangers and therefore the robbery is an unwelcome reminder that violence and crime can still permeate polite spaces.

Hamilton also details the precautions she and her circle take to ensure their safety when travelling around London. Returning from Eva Garrick’s villa in Hampton, with a party that included Charles and Frances Burney, Hamilton comments that ‘we had no disagreeable apprehensions of being attack’d by Highwaymen – for we were a party of 2 Chaises & four & two Coaches & Servts to each wth Pistols’ (HAM/2/10, 107). In the eighteenth century, these measures were neither extreme nor unnecessary. In 1750, Horace Walpole documented similar fears of travelling around London in response to the apparent proliferation of criminal activity not just on the highways, but on the London streets themselves. Walpole writes that ‘you will hear little news from England, but of robberies; the numbers of disbanded soldiers and sailors have all taken to the road, or rather to the street: people are almost afraid of stirring after it is dark. My Lady Albemarle was robbed the other night in Great Russell Street by nine men’.[10] The court proceedings from this incident state that

Lord Bury […] Lady Albemarle, and another Lady were stopped in a coach on the top of Great Russel [sic] street, Bloomsbury, by several persons. His Lordship saw three pistols pointed into the coach, on the side he sat, and gave a particular account of the robbery.[11]

Hamilton had good reason to be cautious, then.

The ‘prudent Chaperone’ and the ‘fluttering crowd’

Hamilton’s response to the theft, and additional references she makes throughout the diary to the ensuring of her safety when travelling around London, reveal a concern not only with encountering dangerous criminals but also with female propriety. This concern is particularly apparent in Hamilton’s justification for leaving Mary Delany’s accompanied by Horace Walpole. Hamilton writes,

I was going away at 9 & as it was still light intended walking home – but Mr. Walpole address’d himself to the three Ladies & ask’d whether they would give their sanction to his taking me home with him in his Coach – they all agree’d that they thought there wd. be no impropriety in it (HAM/2/10, 100-101).

In this situation, Hamilton has to decide whether the impropriety of travelling alone with a man, and any potential repercussions of this, outweighs the risks of walking in the city at night. Though a respectable figure much older than Hamilton, and therefore not perceived as a threat, Walpole must still be given permission to accompany Hamilton by her older female friends.

Hamilton’s diary reveals not only concerns of the impropriety of walking at night, but demonstrates Hamilton’s awareness of her own, and others’, presence in public spaces in the daytime. On 9th May, Hamilton accompanied her younger cousin, Jane Hamilton, and Mary Glover to ‘ye. Gate that leads to ye. Mall’ (HAM/2/10, 32). The Mall was a popular promenading destination, which the travel writer César de Saussure (1705-1783) described as ‘so crowded at times that you cannot help touching your neighbour’.[12] Hamilton responsibly states that ‘I was too prudent a Chaperon to lead my young people to the fluttering Crowd’ (HAM/2/10, 32).

St James's Park and the Mall (British School, c. 1745)

(Image Credit: Royal Collections Trust)

Elsewhere, Hamilton’s concerns extend to the appropriate presentation of the female body in public. While out walking with Anna Maria Clarke, Hamilton reports that ‘Mrs. Vesey saw us from her window came down to ask AM how she did & walk’d ye. length of ye. street without Hat or Cloak she is ye. most innocent unaffected character’ (HAM/2/10, 131). Though Hamilton seems amused at Elizabeth Vesey’s disregard for convention, she is also aware that, for her and her contemporaries, ‘dress was a crucial part of a proper polite appearance’.[13]

For Albinia Hobart, her dress, or at least her jewellery, was a necessary part of her public appearance. However, that appearance also made her Napier’s target. Hamilton’s diary not only provides a gripping record of one woman’s vulnerability in the face of a violent robbery, but is also a source with which to reflect more broadly on women’s anxieties surrounding the regulation of their conduct in Georgian society, and the complex negotiation of virtue and visibility demanded of genteel women in public space.

—

Notes

[1] General Evening Post, 22 May 1784; while the court proceedings refer to the accused as ‘Lapier’, the newspaper reports consistently cite ‘Napier’. The latter is corroborated by the burial record in the Westminster Church of England Parish Registers, 1558-1812 (STJ/PR/8/4).

[2] Morning Chronicle, 25 May 1784.

[3] Old Bailey Proceedings Online, May 1784, Trial of James Lapier (t17840526-19), 732.

[4] Trial of James Lapier, 734.

[5] Trial of James Lapier, 732.

[6] General Evening Post, 22 September 1784.

[7] Tim Hitchcock and Robert Shoemaker, ‘Chapter 7: The State in Chaos: 1776-1789’, paragraph 54, in London Lives: Poverty, Crime and the Making of the Modern City, 1690-1800 (Sheffield: The Digital Humanities Institute, 2020); Hitchcock and Shoemaker cite: Simon Devereaux, ‘Recasting the Theatre of Execution: The Abolition of the Tyburn Ritual’, Past & Present, 202:1 (2009), 127-174, 127.

[8] HAM/2/10, 39-40. Further references are indicated in the text and follow Hamilton’s original spelling.

[9] Robert B. Shoemaker, ‘The Street Robber and the Gentleman Highwayman: Changing Representations and Perceptions of Robbery in London, 1690-1800’, Cultural and Social History, 3:4 (2006), 181-405, 386; Shoemaker cites James Carrick, A Compleat and True Account of All the Robberies Committed by James Carrick, John Malholi, and their Accomplices (London, 1722).

[10] W. S. Lewis (ed.), Horace Walpole’s Correspondence, 48 vols (London, New Haven, and Oxford, 1937-1983) vol. 20, 99, cited in Shoemaker, ‘The Street Robber and the Gentleman Highwayman’, 385.

[11] Old Bailey Proceedings Online, February 1750, Trial of John Stanton and James Webster (t17500228-21), 50.

[12] See Jon Stobart, Andrew Hann, and Victoria Morgan, Spaces of Consumption: Leisure and Shopping in the English Town, c. 1680-1830 (London: Routledge, 2007), 122.

[13] Soile Ylivuouri, Women and Politeness in Eighteenth-Century England: Bodies, Identities, and Power (London: Routledge, 2019), 82.

Emma Stanbridge

December 2021