Christmas has come to Hamilton HQ!

In our first year of the Hamilton project, we’ve found ourselves thinking about ways to mediate absences and distance, and not just in terms of what we find (or don’t) in the archive: our working practices and communications are similarly (socially) distanced in these strange times. We’ve kept up regular virtual contact, and sent cards, birthday presents and even houseplants as a means of maintaining and strengthening the social ties that have developed alongside our professional ones. With Christmas around the corner, we have also been comparing notes on the progress of our Christmas shopping (or lack thereof). Every year I grapple with the concepts of generosity, reciprocity and obligation that go along with the ritualised exchange of gifts. Does this gift appropriately symbolise the nature of my relationship with its recipient? Is it over-generous, conferring too much obligation? Increasingly, we are concerned about whether our gifts are wasteful, or environmentally damaging. While the exchange of gifts is for many, undoubtedly, a source of joy, it can also be a source of anxiety for both giver and receiver.

In his 1925 essay ‘The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies’, the origin point for much of modern gift theory, Marcel Mauss theorised that

in a good number of [civilizations], exchanges and contracts take place in the form of presents; in theory these are voluntary, in reality they are given and reciprocated obligatorily.[1]

Mauss’s theorization of the gift contextualises gift-giving within total, reciprocal systems of circulation that underpin society, cement ties. There is no such thing, argues Mauss, as a free gift. For our December blog post then, it seems appropriate to think about how the giving and receiving of gifts, like the sending of letters, can embody ideas of presence and absence, and bridge distances. During the transcription process, we have found a number of instances of Hamilton receiving gifts from the people around her, as well as occasional instances of her sending a gift herself. The examples I focus on here show the fraught symbolic nature of the gift as a means of defining or establishing relationships that are potentially unstable or ambiguous. In particular, these gifts can tell us about the difficulty of defining relationships between Hamilton, as a (then) single woman, and her male correspondents. As Charles Haskell Hinnant has noted, the giving of gifts between genders is fraught with particular risk:

In gendered exchanges between men and women, the law of gratitude might legitimately be suspended, the gift rejected, and the recipient indifferent to or even suspicious and resentful of the donor’s motives in offering the gift.[2]

From toothpick-case to touching: a slippery slope

Image Credit: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

The gendered exchanges outlined above might not abide by the laws of reciprocity because to abide by those laws may threaten propriety. That potential impropriety is acknowledged by the Prince of Wales (the future George IV) in a letter of 3 July 1779, when he writes to Hamilton that

‘I hope this trifling toothpickcase will not alarm your delicacy’ (GEO-ADD-3-82-10)

By the following month, the Prince’s gift-giving has become a pretext for physical intimacy, pushing the boundaries of that Hamilton’s delicacy:

‘I have order'd ye B[racelet] I hope I shall have ye. happiness my self to bind it upon yr. Arm on Saturday next’ (GEO-ADD-3-82-27, 26 August 1779)

Unlike the toothpick-case, this gift may well have alarmed Hamilton’s delicacy, and with good reason. I won’t dwell here on the precise nature of this relationship (as that would pre-empt future blog posts!) but it does neatly illustrate how the giving, or in this case proposed giving, of a gift has the potential to bridge physical distance and at times breach propriety. By imagining the manner of giving in his letter, the Prince also dictates the terms of Hamilton’s acceptance of such a gift, which is dependent on her accepting his touch.

What Miss Hamilton wrote to the Kitten

(c) English Heritage, Kenwood; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

But how do different relationships inflect the giving of a gift, and what of Hamilton’s other correspondents? Take, for example, William Napier, Hamilton’s self-appointed guardian who refers to her as ‘my daughter and ward’. As Brother-in-law of Hamilton’s aunt Lady Cathcart through marriage, Napier is at best a distant relative, but takes a great interest in Hamilton following the death of her father. Several of Napier’s letters from the early 1770s revolve around a kitten he has given to the eighteen-year-old Hamilton, about whose welfare he often enquires with strange anthropomorphic effect. The kitten becomes a means of teasing Hamilton. Complaining about the shortness of her letters, he imagines instead how she might write to her pet:

‘was the Kitten from N[orthampton] she would I make no doubt be informed that a Regiment was come to town such & such officers were come, some old, others young & handsome & in short we are so Gay or are to be so gay I wish you was here My dear Kitten to partake’ (HAM-1-19-23)

The kitten allows Napier playful access to aspects of Hamilton’s life that she (he imagines) declines to share with him, including a fascination with the regiment of Dragoons who have recently arrived. The anthropomorphised kitten is in keeping with eighteenth-century literary conventions. As Ingrid Tague writes:

Women’s love for their animals rather than for men – presumably more suitable objects of female affection – was a commonplace of writing about pets. Because of this, many writers used animals as an excuse to discuss sex and love, and many of the jeux d’espirit [on women and their pets] were love poems. Following a long tradition, authors were often inspired by the sight of a woman caressing her pet to wish themselves in the animal’s place, or at least to wish she would care for them as much.[3]

Napier sets himself up in parodic rivalry with his gift as a playful means of expressing his jealousy. He continues:

‘pray remember My dearest Mary that I am a jealous friend I wont have any Person male or female in that capacity preferred before me in your confidence write me every thing that concerns your Soul, Mind, Heart & Body without reserve’ (HAM-1-19-23)

The Kitten then becomes not only an excuse for Napier’s correspondence (enquiring after its wellbeing) but also a means of expressing the possessive interest he has in Hamilton under the guise of absurdity, and demanding, through this mock-rivalry (the kitten is after all not ‘any person’), that he be first in her affections. He is also concerned with the reciprocity of their correspondence, writing Hamilton ten-page letters while chiding her for the shortness of hers. Theirs is an unequal exchange, which he emphasises through the symbol of the kitten.

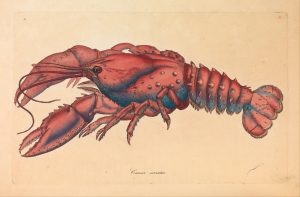

The Love-Sick Lobster

In other cases, the giver offers specific instructions on interpreting their gift. During her time at as a royal sub-governess, Hamilton struck up a friendship with John Farhill, a tutor to the young princes. Farhill’s interest in Hamilton seems to have been romantic, although this was not reciprocated. Nevertheless, Farhill engages in the discourse of gifting to creatively reinforce their relationship. On 28 August 1780 he sends Hamilton the gift of a ‘Tunbridge-box’ for water-colours. In his accompanying note (HAM-1-7-4-1), he plays on the box’s similarity to Hamilton herself and uses this as a vehicle for indirectly praising her and stating his admiration:

I pray you slight me not for I pride

myself in being like you, always the same;

within also I am white, without I am well

-polishd — like you I am sought for by all

who pretend to Taste, and like you I am

loved by all who possess it. It is your's

to give Life, and Spirit to Objects inanimate

my Province also is the same. You

banish Ennui; and so do I — nay more,

we are both much admird by the same

person: (HAM-1-7-4-1)

For Farhill, the gift is also a means of reminding Hamilton of being in his company (the Royal children, along with the tutors and governesses, had recently spent time in Eastbourne together) and of the sincerity of his friendship.

then slight me not: perhaps at

some future Period I may recall to your

Remembrance scenes, which have lately paſsed;

and Persons, whom you have honor'd by

your Friendship: the former, as they have

been ever gay, and innocent, and the

latter, as they are steady, and sincere, may

I trust be reflected on with Complacency, &

Pleasure. (HAM-1-7-4-1)

Farhill is very explicit in directing the meaning of his gift, giving instructions how to interpret the box. Perhaps he means to prevent misunderstanding, and Hamilton does apparently reflect on his friendship ‘with complacency’ as instructed, as their correspondence continues. On 13 September 1782, Farhill writes to Hamilton to thank her for a gift she has sent to him:

Image Credit: The Google Art Project

The Lobster Claws are now before me,

I look on them with pleasure; I

understand you sent them with [a]

smile; they have, I know no[t]

how, a power of soothing the

soul into a sweet Complacency; (HAM-1-7-4-9)

Just like the Tunbridge Box, Hamilton’s gift is one that speaks to shared interests: in this case natural history. Unlike Farhill, though, Hamilton has apparently not provided instructions for the interpretation of her gift, so Farhill must speculate on the sender’s motives, and the mysterious meaning of the gift:

you are a Naturalist & can

perhaps explain this power inherent

in Lobster Claws; for my part I

never saw any like these. (HAM-1-7-4-9)

What Farhill implies here is that the ‘power’ of the gift is not in the Claws themselves, but that they are a gift, and a gift from Hamilton at that. He plays on their shared interest in natural history to invite an explanation (or declaration), willing the gift to represent more, perhaps, than the sender intended.

All I Want for Christmas is You

But what was Hamilton’s own view of the exchange of gifts? So far I have offered examples of gift exchange in relationships that were uneven or unreciprocated, but this was not always the case. Finally, I’d like to turn to her correspondence with her future husband, John Dickenson. Responding to his suggestion that he provide for her in his will in the event he dies before they marry, Hamilton seems wary. In a letter of December 1784 she rejects this offer, resisting the practical, economic reality of marriage that the suggestion has laid bare.

(c) The Irish Times

my Dear friend be assured that this proof of Your love

I never would accept for if it

should please God to end Your

days before we are united & that I should survive You whatever You

might have it in Your power to bestow upon me

except it was some little trifling gift in […] of Your remembrance

I should immediately restore to Your father &

Sisters — let not therefore a thought of this kind

influence Your conduct in this affair — what melancholy

ideas does this raise, but Heaven grant I may

never experience the severe trial of losing You. (HAM-2-15)

All that Hamilton would accept, she says, is ‘some little trifling gift’: romantic symbol, rather than economic substance. This is in keeping with the shift away from dynastic concerns noted by many historians of eighteenth-century marriage towards an ideal of companionate and romantic union. While other correspondents use gifts as ways of closing epistolary distances, imagining a more intimate correspondence or physical closeness, the ‘trifling gift’ gains its meaning not from the gift, but from the giver. The gift can never be a sufficient substitute for the man she loves: it is, at best, a consolation for his absence.

For Hamilton, the symbolic meaning is more important than the substance: it really is the thought that counts. This is a reassuring lesson for those of us panicking about our Christmas shopping: the perfect gift does not exist.[4] Instead, the people who truly love us will find meaning in whatever we give them.

Cassie Ulph December 2020 --

[1] Marcel Mauss, The Gift: the form and reason for exchange in archaic societies, trans. W. D. Halls (Routledge: 1990), p. 3.

[2] Charles Haskell Hinnant, ‘The Erotics of the Gift: Gender and Exchange in the Eighteenth Century Novel’, in Zionowski and Klekar (eds), The Culture of the Gift in Eighteenth-Century England (Palgrave: 2009), pp. 143-158 (144).

[3] Ingrid H Tague, ‘Dead Pets: Satire and Sentiment in British Elegies and Epitaphs for Animals’, Eighteenth-Century Studies 41:3 (Spring 2008), 289-306, (294).

[4] Unless it's an Xbox.