In this month's blog post, Tino Oudesluijs reflects on how the challenges of transcription connect the eighteenth century to the twenty-first.

Unlocking the Hamilton Papers is well underway in the transcription stage of the project, and the PDRA team (Cassie, Christine and I) come across a wide variety of letters, notes and other documents, as well as some drafts and copies (see also the University of Manchester Special Collections website here). As pointed out by Cassie in the previous blog, transcribing and coding these documents can be quite challenging. As was done in the Image To Text project before, we try to reproduce the spelling, punctuation and lay-out of the texts as exactly as possible. In addition, we mark up the transliterations using XML (eXtensible Markup Language) in Oxygen according to a project-specific subset of the TEI (Text Encoding Initiative) guidelines.

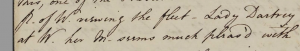

A big part of the transcription process includes checking each other’s transcriptions, as a first transcription can contain various mistakes and errors (we are only human after all), such as misspellings (there is no autocorrect in Oxygen!) or forgetting to add an element or attribute to the text during the mark-up process. One mistake I recently managed to catch before sending my transcription through to the checker concerned a so-called Augensprung (‘a jump of the eye’) in HAM/1/12/72 (a copy of a letter from Mary Hamilton to Charlotte Finch). This basically means I missed a large chunk of a line of text, when during a ‘jump’ between the image of the original letter and the transcription in Oxygen with my eyes, I continued from the wrong letter, in this case W:

As a result, my transcribed line read ‘P(rince) of W(ales) her Majesty seems much pleas’d with …’ etc., instead of ‘P(rince) of W(ales) viewing the fleet – Lady Dartrey …’ etc.

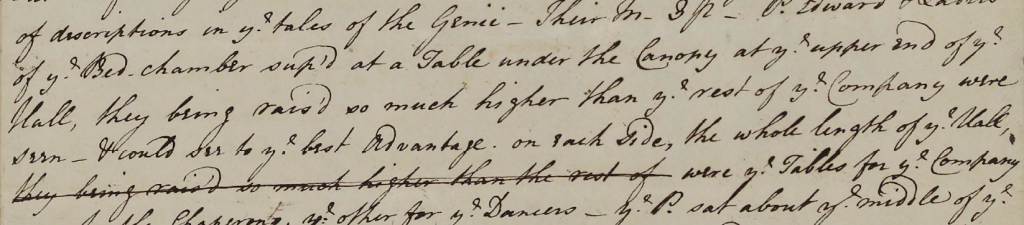

Interestingly, exactly this kind of mistake was made by Mary Hamilton herself when she copied this very letter:

Here Mary Hamilton wrote and subsequently deleted ‘they being rais’d so much higher than the rest of’, which can be read two lines further up as well (in the line starting with ‘Hall, they…’). Clearly Mary Hamilton copied the wrong line here when her eyes were busy jumping between the exemplar and her own copy.

Besides seeing that Mary Hamilton was dealing with the same kinds of issues as we are today when creating copies of these letters in XML, mistakes like this one can also tell us something about the original letter (which we don’t have). In this case, Mary’s erroneous copy of the line reveals that the original likely did not have ‘they being rais’d so much higher than the rest of …’ at the very start of the line like here in the copy, but rather on the same line as ‘of ye Hall,’, which phrase is present just before the miscopied line as well as what should have been written instead (‘were ye Tables for ye Company’). Similar to how I miscopied my line due the presence of ‘W.’ at the same place in two different lines in the example above, Mary must have looked at and copied ‘… of ye Hall,’ before looking back at the original and subsequently copying the wrong line. Furthermore, it is interesting to notice the differences between the two copied lines in Mary’s version: both have raised as ‘rais’d’, indicating that the original likely contained this spelling variant, but the first copy has ‘ye’ for the, whereas the second (cancelled) copy has ‘the’, which indicates that Mary likely did not make a direct copy of the original but varied a bit (at least regarding spelling). This is not surprising, as direct copies (i.e. copies that are almost without any changes from the original at all, be it in spelling, punctuation, syntax, morphology or vocabulary) are rare in the history of the English language, at least when it comes to written texts.

Even in the project, in which we try to reproduce the spelling, punctuation and lay-out of the texts as exactly as possible for both the diplomatic and normalised edition, it is almost impossible to create exact copies of the texts. Besides the obvious material differences between a letter and a digital format, as well as not being able to visualise the differences in handwriting due to the fact that we use a fixed font, we frequently have discussions on how to best transcribe the punctuation, lay-out, or various symbols that do not really match any of the ones available to us in Oxygen. In addition, despite the rich assortment of TEI tags that allow us to code for all sorts of things the author did when writing their letter (think of additions above or below the line, deletions, substitutions, abbreviations, etc.), we always seem to eventually stumble upon a writer who did things ever-so-slightly differently, leading into more discussions on how to best transcribe and mark-up the texts.

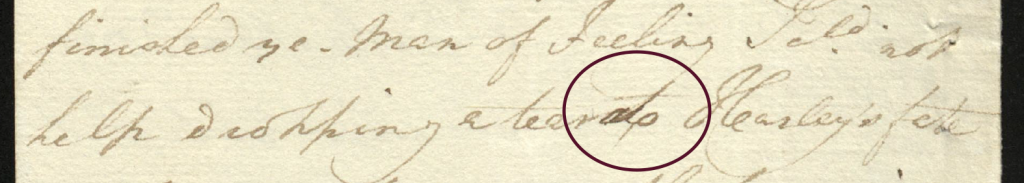

One example that comes to mind occurs in GEO/ADD/3/82/59, where George, Prince of Wales, added an ‘a’ before ‘to’ in the line ‘… I could not help dropping a tear at(o) Harley’s fate’, thus indicating he preferred the preposition ‘at’ after he had already written ‘to’ (which is also indicated by the spacing of the words).

Normally we mark-up substitutions like this by indicating which word was deleted, and which one was added (usually a writer writes over a word or deletes it before continuing with the preferred word). However, here it can be argued that the word ‘to’ was not completely deleted, as the ‘-t’ was used to form the word ‘at’. On the other hand, the word ‘to’ stopped being the word ‘to’ after the change had been made by George, so how do we code for this kind of substitution? On the word level, or the character level? We ended up deciding to tackle this on the character level, thus indicating the addition of ‘a’ and the deletion of ‘o’ rather than the addition of ‘at’ and the deletion of ‘to’, but one can easily argue that going for the word level in this case would have been an equally valid approach.

As we are creating a large corpus of letters, notes and diaries for future research in multiple disciplines, we aim to be as consistent as possible in our transcription practices. However, when transcribing thousands of documents written by dozens of different people, we are frequently confronted with new and unexpected cases that highlight the limitations of faithfully recreating the original texts in a digital format (which is also why we include images of the texts themselves in our online edition). As such, working on projects like this reminds me that, even where the digital format allows for many more opportunities research-wise (especially in the field of corpus linguistics), there isn’t anything quite like the original texts to give you the relevant (material) context and transport you back to a time when Mary Hamilton was similarly making mistakes when copying her letters.

Tino Oudesluijs

June 2020